The Fire of Life

By Sue Donoghue, DVM, DACVN

Citation:

Donoghue, s. (2002). The Fire of Life. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, March 2002. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/02Donoghue.html)

Introduction by the CHAMELEONS! staff:

We are very pleased to have Dr. Susan Donoghue as a regular contributor. Her qualifications as a reptilian nutritionist are unparalleled anywhere and her down-to-earth approach to what can be a complicated subject is truly refreshing. Dr Donoghue is a widely published author in a number of technical and trade publications and the advice she contributes here is priceless! Dr. Donoghue is the founder of Walkabout Farm - a company that markets an array of speciality nutritional supplements for reptiles and amphibians. Dr. Donoghue is an avid collector and breeder of several species of reptiles in addition to chameleons including turtles and tortoises of which she has a very impressive breeding collection.

The Fire of Life

There is a flame burning deep inside every chameleon. It is present as soon as an embryo is formed, and lasts until the moment of death. This metaphorical fire involves every aspect of chameleon life. Climbing a bush? The fire provides the muscle power and nerve transmissions to move limbs. Zapping a fly? The fire provides for not only tongue muscle contractions, but also the necessary digestive enzymes, transport proteins, and intestinal secretions. It keeps the chameleon's heart beating, eyes rotating, toes clasping. It is essential for a chameleon's production of antibodies, skin cells, toenails, and thoughts. It is the fire of life, a term coined by Max Kleiber, one of the best 20th century scientists.

The Forest and the Trees

It's morning and you're feeding your chameleons. Is today's fare crickets or silkworms? Is it a dusting day or not? Is the dust vitamins and minerals, or just calcium?

Much of the effort in planning meals for a chameleon involves prey variety and supplementation, as well as delivery methods, prey size, and palatability. It's enough to make one lose sight of the primary reason for feeding. It isn't calcium or carotene. It is calories.

Let's say you are feeding crickets today. Your Ambanja Panther zaps a cricket, drawing the prey into its mouth, and chewing the insect. Can you see calories spilling from the mashed cricket? Not directly, but you will see evidence of fat, and a careful dissection of crickets will also show you protein. It is the breakdown of these fats and proteins that produce calories. And it is these calories that determine so much about your chameleon.

Counting Calories

Everything your chameleon does require calories - climbing, eating, and thinking; making cells, antibodies, and embryos. Even when sleeping, your chameleon is burning calories. Just as you may require, for example, 2000 calories daily to do all you need to do, so your chameleon needs a certain number of calories daily. To obtain sufficient calories, you eat fat, protein, simple and complex carbohydrates, and perhaps drink alcohol. Chameleons use fat and protein for calories. It is calorie production, through the breakdown of fat and protein, which fuels chemical reactions inside cells. And it is these chemical reactions, in their summation, that are your chameleon.

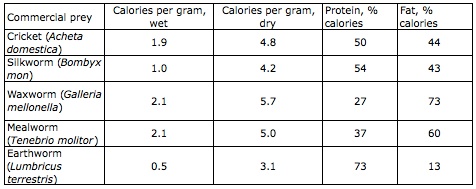

Estimates from chameleon prey in the wild suggest that chameleons take in about 40-50% of their calories from protein and about 50-60% from fat. Commercial prey that approximate these 40:60 and 50:50 ratios are considered to be used most efficiently by chameleons.

The following chart provides data on calories, protein and fat in prey fed to chameleons. Data presented on a 'wet' basis refers to the contents of the invertebrate as is, including its water content. Data presented on a 'dry' basis refers to the contents of the invertebrate after water has been removed. Because water contents vary between foods yet provides no calories, data on a dry basis are preferred by scientists because it makes comparisons between foods easier. When studying metabolism and nutrition, one further step is needed, and the data are presented on a 'per calorie' basis. I use data on a wet basis when making up recipes for chameleon owners, data on a dry basis when comparing different foods, and data on a calorie basis when working with sick chameleons or studying chameleon physiology

There is no need to commit these numbers to memory. In the real world, the actual values for calories, protein and fat vary quite a bit between specimens of a species and over time within individual specimens. Details will follow in subsequent columns.

FAQ: Wax worms are often recommended for adding weight to a thin chameleon, but are not recommended for daily fare. Why?

Note the data in the above chart. Wax worms have more fat than, say, silkworms - 73% vs 43%. Because fat contains more than twice as many calories as protein, gram for gram, wax worms contain more calories than silkworms (5.7 vs 4.2 kcal/g dry, or 2.1 vs 1.0 gram as fed). So if your chameleon eats 5 grams of wax worms it will take in 10 calories. If your chameleon eats 5 grams of silkworms, in contrast, it takes in just 5 calories. As fat increases, protein decreases in prey. Because protein is only 27% in wax worms, the prey are unsuitable for full-time feeding. Your chameleon needs more protein in order to meet its needs for amino acids.

Eye of the Beholder

Most of the time, we feed a certain amount of food to achieve a desired body condition - this is a tested and true method for feeding all sorts of animals: The eye of the farmer feeds the ox, and so on. If a diet is complete and balanced, we don't measure calories specifically, but instead we adjust the amount of food offered in order to increase, decrease or maintain body weight.

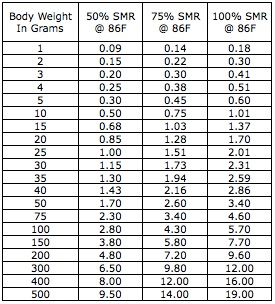

When calorie counting is needed, there are several methods for determining the calorie needs of a chameleon, and comparing this to the number of calories eaten in a day. Mostly, we use equations (instead of laboratory machines) to estimate daily calorie usage (otherwise known as metabolic rate and measured in calories per day), and from these equations generate calorie charts. Here's one for insectivores that I use in my work:

Standard Metabolic Rate (SMR) Kcal/day = 32(BWkg0.75)

If I'm working with a panther chameleon weighing 100 grams, I first estimate from the chart that it needs at least 5 to 6 calories daily. These numbers were derived on inactive lizards kept in the dark. Thus more calories will be needed (from 25-100% more) if the chameleon is growing, forming eggs, very active, or kept very warm (these activities increase metabolic rate, hence increase the number of calories used per day). Fewer calories will be needed if the chameleon is sick, kept in cool temperatures, or is confined with little activity. Because most of the clients I work with have sick animals, I maintain the chart with fractions (50 and 75%) of standard metabolic rate.

Adding Weight to Chameleons

Let's say one of your chameleons is looking thin. He is a long-term resident of your collection and has been on a good preventive medicine program, including yearly exams and fecals. The chameleon's tail-base appears more rectangular than oval, ribs are highly visible, and legs are stick thin. The animal is alert, eating and drinking. I recommend weighing the animal first, then using the above chart to estimate the calories your chameleon should be taking in. Then list the type and number of prey fed. You can then compare calories in (from prey, first chart) to calories out (metabolic rate, second chart).

If it appears that your chameleon is taking in just enough prey to meet his needs at his present weight, try feeding more prey. This is often accomplished best by adding meals instead of increasing meal size. If, however, it appears that your chameleon is taking in calories in excess of what is needed, and he is not gaining weight, it's time for a visit to the vet for a thorough exam.

FAQ: Why can't I just add a few more crickets when I feed? It would be much easier than adding another meal later in the day.

Although I'm unaware of hard data from research labs, all indications are that chameleons have relatively small stomach volumes. My own experiences in feeding trials with healthy chameleons, assist-feeding sick chameleons, and careful dissection during necropsies suggest that chameleon stomachs have limited capacities. You'll see far less regurgitation, and far better recovery of weight, from an added meal. This technique isn't just for chameleons - almost all animals (including humans but with the possible exception of large snakes), better tolerate many small meals rather than fewer larger meals.

Taking Weight From Chameleons

Can chameleons become obese? Rather than re-inventing the wheel, we look at what is known for other animals. Most overweight animals are simply overweight, with about 10% or less categorized as truly obese. It is the truly obese that suffer ill health and, indeed, most of the diseases of obesity are uncommon in chameleons. Our chameleons' arteries don't clog, nor do they develop Type II diabetes. They don't smoke or drink. Chameleons, however, do reproduce. And concerns about overweight chameleons center on effects of high calorie intakes on egg production in females. We'll cover this in detail in future columns. For now, know that the primary nutritional goals of some chameleon breeders is to find ways to limit (excessive) egg formation by limiting calorie intake, while finding ways to meet metabolic demands once eggs have been formed. This is a challenging and often daunting task, but key to future chameleon herpetoculture.

Goals for weight loss aim for slow, consistent weight loss. Try for a loss of no more than 1% body weight per week. Expect the process to take up to 12 months. Reduce meal sizes, rather then number of meals. Evaluate the chameleon every week, and reconsider goals if necessary. During periods of weight loss, reproduction often shuts down, and your chameleon may have already formed eggs, which can lead to dystocia. Unhealthy side effects of weight loss include negative nitrogen balance which impairs synthesis of antibodies, enzymes and cells. Proceed with caution.

It's All About Calories

The fire within your chameleon is its metabolic rate. It plays a role in every aspect of chameleon nutrition, hence it is the place to begin in-depth discussions of chameleon diets and feeding management. In future columns we'll cover nutrients such as calcium and vitamin A, design of feeding programs, tips for very small and very large collections, nutritional impact on reproduction, growth, and illness, metabolic (hence nutritional) differences between species, assist feeding, and so on. It all begins, however, with the flame within. The calories burned by your chameleon, keeping its fire of life fueled, is the basis upon which nutrition is built. We're off to a good start.

Sue Donoghue, DVM, DACVN

Susan Donoghue, VMD, DACVN specializes in the research of herpetological nutrition. She is the founder of Walkabout Farm. She can be reached at

Walkabout Farm

PO Box 625

Pembroke, VA 24136

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com