Furcifer minor in captivity

By Christopher V. Anderson

Citation:

Anderson, C.V. (2002). Furcifer minor in captivity. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, May 2002. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/02MayAndersonMinorCaptive.html)

Furcifer minor in captivity

Captive Status

As with the majority of other Malagasy chameleon species, Furcifer minor was banned from export in 1995. Technically, no legal exportation of this species could occur from Madagascar after this time. There have however been at least two questionable shipments that have left Madagascar containing F. minor in them since the ban was imposed. Large quantities of F. minor, along with other species, entered the market before the imposition of the ban and remarkably, only a handful have made it. It is truly a shame that with so many imported into the reptile market that they were not established and that so few still remain in captivity. With so few working with this species and the extremely limited and decreasing gene pool, it is tragically inevitable that this species, with the exception of the occasional illegally smuggled specimens, will disappear from captivity in the foreseeable future. This event can at best be seen as an absolute calamity for the keepers who have worked so hard to establish them and worse still, for the animals themselves.

Captive Husbandry

The author's personal preference for housing all chameleons is to let them decide, as they do in their natural state in the wild. The author prefers to set his animals up in a way that allows the animals to indicate what they like rather than to conform to the experiences of others and not allow for individual variation within the species. This species is housed individually in 17"x30"x48" (44cmx76cmx122cm) tall screen cages elevated so the top of the cage is approximately 6' (180cm) off the ground. Ambient light is provided with a fluorescent tube light high in UVB output while a 150watt incandescent bulb provides heat. Wattage for the basking bulb should vary based on the temperature of the area one is located. This setup allows for the cage to range in temperature from 70-85 degrees Fahrenheit (21-30C), on average, depending on where the chameleon is. Night temperature drops into the 60s Fahrenheit (18C) are routine with drops into the mid 50s (12C) not unheard of or met with ill effects. On occasion the temperature in the cage has been known to reach as high as 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35C) with no effect to the chameleons as long as hydration was adequate. In this type of setup, the author has found that healthy chameleons will move around to areas of their liking throughout the day as they do in the wild. He has found that this minimizes illnesses caused by excessive or low heat and that the chameleons seem to be much more active and healthy when housed in this fashion. It should be noted however that sick animals do not do this and in this type of setup, ill chameleons can suffer if they are not identified and placed in a more controlled setup. When the discussed setup is used, it is vital to keep an eye on your animals for signs of illness.

Hydration was provided through misting and drippers. Every morning the cages are heavily misted with luke warm water for at least five minutes. A dripper is then started which runs for about 3-4 hours. In the mid afternoon, the cages are once again misted although not as heavily and the drippers restarted. Finally, about an hour before the lights are turned off the cages are misted once again but only briefly to wet the plants and increase humidity. The time between misting must be sufficient for the cage to dry out with the exception of the area where the dripper is. This species seems to have high hydration requirements but at the same time requires an environment that is relatively dry (when compared to forest species) with medium humidity throughout the day as was seen in their natural environment.

F. minor are easily pleased eaters. The author has never had his animals turn down any form of food offered and they are always eager to eat as much as given. Unlike many species, F. minor appears to have no problem eating for an audience. They will readily eat from their keeper's hands and run toward the cage opening when they see that they are being fed. On the other hand, if they see a hand without food they become very shy and try to escape or turn to the other side of a branch. This is however a very alert species that, in the author's opinion, have greater personality than most other species and are very interesting to observe.

The author has found his F. minor to be very shy about breeding. The male is quick to display, as is the female, but hesitates to advance with the presence of anyone. One attempt, that consisted of a number of days of cohabitation of the male and female, resulted in what he was sure was a successful breeding. Petr Necas, who visited afterwards, agreed that she appeared to be gravid. This attempted ended up being a false gravidity and the author is now awaiting the eggs of a final attempt after the unexpected death of his male, believed to be related to gout, caused by improper feeding before he acquired the animal. Time will tell if her gravid appearance is true or if yet another dead end has been reached for the continued efforts to maintain this species in captivity. If she is in fact gravid, the next obstacle will be related to egg laying, with many keepers loosing females to egg binding, a condition this species appears to be especially prone to.

Overall, the author has found F. minor to be quite enjoyable to keep as captives. Their absolute beauty along with their personalities make them a species which he has truly enjoyed working with. These precious little creatures are a extraordinarily interesting, beautiful and a true gem. It is a highly devastating notion that they might not be around in the future, both in the wild and in captive collections, and the past failures, which could easily have been successes, are even more upsetting.

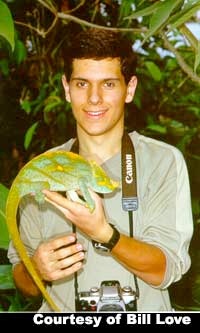

Christopher V. Anderson

Chris Anderson is a herpetologist currently working on his Ph.D. at the University of South Florida after receiving his B.S. from Cornell University. He has spent time in the jungles of South East Asia, among other areas, aiding in research for publication. He has previously traveled throughout Madagascar in search of, and conducting personal research on, the chameleons of the region. He has traveled to over 35 countries, including chameleon habitat in 6. Currently, Chris is the Editor and Webmaster of the Chameleons! Online E-Zine and is studying the kinematics and morphological basis of ballistic tongue projection and tongue retraction in chameleons for his dissertation. Chris Can be emailed at Chris.Anderson@chameleonnews.com or cvanders@mail.usf.edu.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com