Madagascar, A New World

By Allison Banks

Citation:

Banks, A. (2002). Madagascar, A New World. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, May 2002. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/02MayBanks.html)

Introduction by the CHAMELEONS! staff:

Traveling is always an enriching experience. The opportunity to go visit a new culture, the people of another country and its flora and fauna, offers the traveler the chance to grow and expand their awareness. For a hobbyist the ultimate dream is to experience first hand the world of the animals in their care. Allison Banks joyously shares her exploration of her travel experiences in Madagascar, using her own stamp of humor and insight to bring a fresh and oftentimes surprising look of her views and impressions of this remarkable island.

Madagascar, A New World

After two years hoarding tax returns, vacation time, and working a second job at a reptile specialty shop (I was there once a week getting supplies for 6 spoiled chameleons anyway), I was finally dragging luggage through an airport on the way to Madagascar with Ken Kalisch and Ardi Abate. The three of us met for the first time in person at that airport. We were off to visit the Eastern Coastal rainforests to look for white and yellow-lipped Calumma parsonii, Calumma parsonii cristifer, and any other species that was gracious enough to be found. By the time we left Paris our rumps were numb, and as Anne Baxter once put it "we were furry toothed and poached of eye". Only 13 hours to go! During the next leg of our flight, Ardi attempted to teach me essential Malagasy. The result wasn't pretty and I can't blame it on jet lag. They quickly decided as long as I could smile and say "misaotra" (thank you) there wouldn't be international alarm.

My friends graciously invited me on this trip to apply my "biologist's eye" to observations they made in this trip to hunt for Parson's chameleons. Where were they being found in these days of degraded and declining mature rainforest habitats? Were the longstanding ideas about their habitat requirements accurate or even meaningful? If Madagascar continues to consider its native wildlife a trade commodity, how will they ever know if their glorious species can tolerate collection on top of habitat degradation?

For most of my adult life I have studied and worked to protect wildlife of western North America and Alaska. It's one thing to roam around within a familiar continent and know almost instinctively what creatures are found in various temperate habitats and why they occur where they do.

Madagascar was something else again; a different planet where almost nothing I would see was remotely related to home. I wondered how much of my biological background would seem absurd there. I've lived in places considered dangerous; arctic tundra, remote deserts, and high altitude mountains. This wouldn't feel threatening, just thoroughly alien, where even the taste of the dust on my face had never been encountered before. One startling thing I remember was to look at a familiar potted fern sitting on a bungalow porch railing and realize it may not even be a fern, as I know it! There is a fascinating ecological idea called "concurrent evolution" that basically says that species entirely isolated from each other genetically may be shaped by environment and usage to look or function very much the same. For example, there is a bird native only to the Mediterranean region that looks and behaves amazingly like the unique and unrelated wrentit of southern California; the only Mediterranean climatic region in this hemisphere. Was my potted fern a native, isolated from any other continent for millions of years, or an introduced exotic weed belonging halfway around the globe? In this time of global community what does exotic or native really mean?

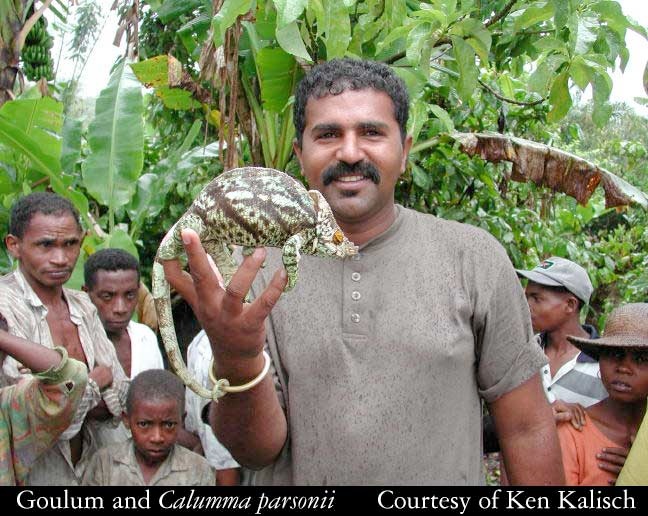

We landed in the capital, Antannanarivo, and were met by Ken and Ardi's long-time friend and guide Eugene Goulam at the stifling, smoke-fogged airport. This was late October, the end of the dry season. Goulam and his cousin Popitsu met us with solemn handshakes and kisses, corralled the luggage, haggled with customs, and bartered for Malagasy cash with the black market moneychangers slinking around the parking lot. We squeezed luggage and 5 adults into and onto a Peugeot (sp??) wagon and took off to check reservations and permits and to stock up on delicious Malagasy "take out" snacks for the drive. These were often sambosas, nim (a little like fried pot stickers or eggrolls), jackfruit, bananas, green coconuts, citrus, homemade potato chips, nuts, and ice cream.

I'd been sitting on planes for about 25 hours, but hardly cared. There were strange birds calling overhead. Drongos, common minahs and red futias flashed from roadside trees to telephone poles. No one around us spoke a language I could understand. There were gemlike day geckos on house walls. I had no sense of time (it was sunny and hot, so it must be day), the malaria medicine, Chloroquine made me feel disembodied, but the city's huge jacarandas were in glorious bloom and this was as far from home as I could go without getting closer again.

The first wild chameleon we saw was a male Furcifer willsii trying to get from one forest patch to another in a logged over area. We almost ran over it with the car. The 4 chameleons I remember most clearly were this F.willsii, a furious Furcifer bifidus, king of his bush who bluffed and threatened us with great vigor, a Calumma brevicornis we toted back into the safety of the forest on our shoulders, and a massive, male yellow-lipped C.parsonii who gazed at the ring of camera lenses, waving hands and alien faces with gentle dignity (and a crushing grip!). Other personal favorites were a pair of possibly courting Furcifer balteatus and a tiny orange juvenile C.parsonii found in a white flowered shrub.

When we finally released the F. willsii after many photos I watched as it silently disappeared into the leaves. Was it more truly a chameleon because it still moved within the ecosystem it affected and was affected by? Maybe this is philosophical drivel, but is a California condor really a condor without its mountain to soar over?

As we traveled the secondary roads of the East Coast we asked villagers what chameleons were to be found locally. Occasionally someone would take us to see a Parson's chameleon or bring one to the car. Touching chameleons is not something most Malagasy do willingly, as they believe the gentle animals are bad luck. Ironically, it may be one reason these fairly defenseless lizards have survived human settlement at all. So often, humans just obliterate any creature they consider a nuisance or a threat. A man's neighbors might consider him brave or foolish to bring us one small chameleon clutching the tip of a long stout branch. They would shout with laughter and disbelief when we let them crawl on our arms and shoulders without fear. We would end up with the whole village surrounding the car waiting to shake hands with shy courtesy.

What were we seeing here? When a Parson's chameleon was found near a village or in a coffee grove what did that tell us about the species? If we found 20 or 30 such animals in the same situation what does that mean in terms of the regional population? Is it coincidence? Chance? Is this a true sample of the surrounding population? An unintentional bias in our questioning? There is no way to be sure. We would have to survey every square mile of an area uniformly, considering every type of habitat equally before we could say what the population of any creature there actually was. Trying to census any animal by using roadways will trap the biologist in a mess of data bias. But, this was not really Ardi and Ken's intention of course.

I know from personal experience just how hard it is to figure out what a population of any wild animal is doing. Many, many professional wildlife biologists have spent careers gathering literally years of data on a specific animal (did I mention many?) and still cannot answer basic management questions about them. Even having very detailed information on exactly what habitat is needed and in what amounts and the exact productivity of breeding animals, a manager can still be misled into thinking his species of interest is healthy. Believe me, it happens all the time. For creatures as little known as Malagasy chameleons there is almost no credible data to answer these questions. What these species require to persist in the wild is literally unknown. Our trip added information to the file and the contacts we made with villagers will only help them appreciate their resources. It takes years of dedicated, focused field work on productivity, habitat requirements, behavior, hunting and breeding requirements, food selection, plus analysis of changing habitat conditions before a defensible plan to manage them will result. It's going to take more than the efforts of any one person or study. Studies can be biased intentionally or by accident. The wrong questions can be answered, data skewed to make a political point. If the results from one study don't support someone else's hopes the data suddenly gets labeled "flawed, not based on good science" etc. One person's science is another's personal opinion depending on their agenda.

We did see a few very young juvenile Parson's chameleons. This is good news, as the habitat they were found in was not in pristine condition. It had been severely altered long before these animals were born. All this really tells you is that there are some adult chameleons breeding and producing young. What it DOESN'T tell you is whether enough of the regional population of chameleons is also able to produce young. It doesn't tell you whether those young individuals ever survived long enough to breed and replace themselves. THAT is by far the most important information! It doesn't tell you whether the regional population is maintaining itself or slowly dwindling away, becoming genetically damaged to die out over time, or whether it persists in isolated, fragile groups easily wiped out by a fire, collection, floods, disease, or inbreeding. Parson's chameleon is fairly long-lived, making it a really valuable species to study. But, what may hold true for this chameleon may not be applicable to any other species. You would have to start at the beginning again.

Conservation-oriented visitors to Madagascar don't just pay airfare to see this land. They pay a price in heartbreak as well. Driving through denuded mountains with their massive erosion, through overgrazed and almost sterile valleys whose soil is mostly fit for making bricks, seeing the silt filled rivers, shanty towns, work worn people and equally gaunt domestic livestock made me feel quite undeserving, spoiled, and embarrassed. Ardi had warned me about what I would see and feel and she was right. This is a place where everything one does has an uncomfortably direct effect on the land. If I insisted on having hot water for laundry a wood fire would probably heat it. Where did the wood come from? Most likely a fast-fading patch of native forest with its cadre of dependent organisms found nowhere else on earth. If I gave a 10,000-franc note to a child who finds me a chameleon to photograph was I teaching her to respect that chameleon or to cause its death? If I choose zebu off a menu instead of vegetables I might change the hotely owner's diet for a week. What happened to all those discarded plastic Evian water bottles we used? Actually, they get used until they crack by people who have nothing else to carry liquids in.

It is easy to blame a remote nation for bad environmental stewardship and to judge the actions of its people without ever understanding the choices they must make. Most people we talked to in rural areas knew cutting more of their rainforest to plant red rice would lead to environmental trouble, but what choice did they have? Growing families need rice or the money from it. More rice requires more cleared land. People knew that imported eucalyptus didn't allow much of anything to grow underneath it, that it was useless for lumber because of its spiral grain, and that it was replacing slower growing native forest, but what could they do to stop it? They needed a quick-growing tree for firewood, burned it to clear land for farming and grazing, and ended up spreading it even faster. Many people we asked felt it was wrong to sell wild caught native animals to travelling collectors, but when the collector offers parents enough money to buy supplies the schools require before their children can enroll, who could pass that by?

While you're chewing on these massive questions here's a few more:

Even if biologists actually figure out how many Malagasy chameleons exist today that is only part of the equation for managing them over time. Who's going to develop the needed repeatable census? Who's going to get the funding and manpower to carry it out? There will always be environmental change and damage to analyze to keep the population data meaningful. Who is going to consistently educate the people who change their habitat, their food sources, and their environmental health? You can't protect any organism without convincing humans who affect or share the land just why (and how) this should be done. Even in a relatively well-informed nation like the USA it takes years of effort to protect one endangered species from extinction. I know personally, as I've worked on such contentious management issues as the spotted owl, desert tortoise, Hawaiian endemic forest birds and plants, and Steven's kangaroo rat.

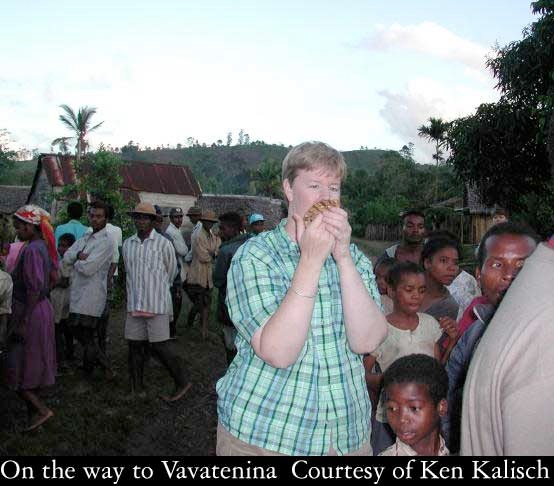

At the end of our journey we finally coaxed superstitious Popitsu to hold a tiny, jewel-toned carpet chameleon. A male F.willsii made it safely across that scorching road with help from an overexcited human. The Peugeot lost its battered exhaust (we kept tying it to the frame again and again until the poly rope burned through) but finally got a new one. A gentle shifaka in a private zoo held hands with 3 Americans. An elderly woman in a tiny village saw herself and her grandchildren in a digital camera screen. 100 kids got toothbrushes and pencils for school. The residents of Vavatenina now know Americans are crazy because they fly halfway around the globe to touch fady lizards. I have a faint scar on my hand from the grip of a massive Parson's chameleon. And when I open my cherished handcrafted chess box at home the scent of wood smoke, cloves, cinnamon and vanilla take me back to this new world.

Allison Banks

Allison Banks is currently a wilderness management planner for Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in SE Alaska. She has a degree in wildlife Biology and Management from Oregon State Univeristy and has worked for the US Fish and Wildlife Service for about 15 years in National Wildlife Refuge System management and endangered species recovery programs. She started her chameleon addition in 1994.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com