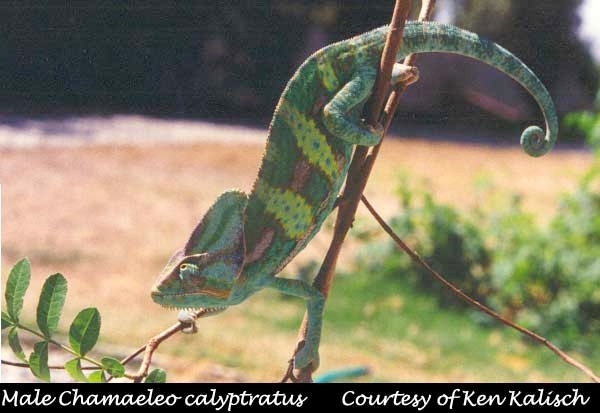

Chamaeleo calyptratus - Veiled FAQ

By Ken Kalisch

Citation:

Kalisch, K. (2003). Chamaeleo calyptratus - Veiled FAQ. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, March 2003. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/03MarKalischVeiled.html)

My chameleon just exploded when I put him on my plaid shirt!!!!!!!

or ......The truth about what you really need to know about your Veiled Chameleon!

The old saying that if you put a chameleon on plaid it will die due to it's inability to match the background is a long standing old wives tale and yet this misconception continues to be propagated in news reports and even in newly printed biology books. Many people continue to ask about the amazing believed ability of the chameleon to match its background surroundings. People familiar with chameleons know that the chameleon's coloration is induced by environmental cues such as temperature, lighting and behavioral indicators. The manifestations of the coloration of a chameleon have nothing to do with what it is sitting in or around. Yet this concept still persists. Like the misunderstood coloration concept, there seems to be a similar ongoing confusion with one of the most commonly kept chameleons Chamaeleo calyptratus, the Veiled Chameleon, creating confusion and taking many hobbyist in the wrong direction.

The intent of this article is to increase the basic awareness of their captive management and to clear up some of the ongoing confusion surrounding their care by answering questions asked by our readers about Calyptratus and their care ...

Q. I want to purchase a Veiled Chameleon, what should I do to make sure I buy a healthy one?

- Joe Sullivan, SD, CA

A. So much has been written guiding a potential owner to make a good chameleon selection and with calyptratus, the rules aren't much different.

1. I can't say enough about doing all the research on the species before you purchase it!!! Read everything you can get your hands on. Success with the species is about knowledge and there are all kinds of ways to access this information. Talk to anyone that currently owns them, join a chameleon list-serve and ask questions there, buy a book (or more) on the species (see the book review in this issue). Go online and surf the Internet, there are vast amounts of information there to be unearthed. I have always enjoyed the search and research for information on my chameleons and I found that there was a whole new set of rules I had to incorporate to every new species that I worked with. Through this kind of exploration the overall understanding of the chameleons requirements are developed to a much deeper level. Just looking at where they live in the wild, what the rainfall is, what the temperature ranges are (both day/night and seasonally) all will add to the overall understanding of their requirements. The effort it takes to do the research pays off in the increased understanding and success of their care.

2.Know the breeder that you plan to buy from. I don't mean be best friends, but understand how they care for their chameleons. It is imperative that in order to have a strong and healthy adult you must start with good stock. Ask what, how much and how they are fed, what kinds of supplementation they are given (if any), what type of lighting they are exposed to (natural sun or artificial...and then what type of artificial lighting was used). How your newly purchased baby was raised and how the parents were raised will have long-term effects on your success overall. I even think that a good breeder should be open to giving you the names and phone numbers of other people that have previously purchased chameleons from them so you can discuss their experiences with the buyer and the chameleons purchased. They should also have the commitment to helping you with your chameleon when and if the need arises. All these are good indicators of someone that is committed to doing right in the care of their animals.

Clearly from all I have said this is not an impulse purchase. It takes time thought and discipline to pull it all together.

While we are on the subject of new acquisitions and all let me also address two other common mistakes with chameleon care that occur with the new keeper of chameleons. They are cohabitation and purchasing unrelated stock.

I am often asked it is OK to keep chameleons together (male/female or female/female). The truth lies in understanding the nature of the chameleon. Chameleons for the most part are solitary reptiles. They come together for breeding and may stay together for a short time while this occurs. No one should plan on keeping their chameleons together on a permanent basis. They should be brought together for the purpose of breeding and upon completion, returned to their own cage.

In the case of housing two females in the same cage, the possibility exists, but again they may not be compatible and need to be housed separately. Don't expect to keep them together, always have another cage available.

The result of trying to house chameleons together is they are being forced to be constantly exposed to a stressful situation by being in such close proximity to another chameleon. The ongoing stress can manifest in pacing the cage, refusal to eat and eventual illness. In the wild the chameleon could just walk away from the other chameleon, in captivity we have removed that option.

It is very important to observe any introductions of chameleons. The risk of aggression is very real. Even when there are not any obvious signs, watch for coloration changes. If the coloration darkens or becomes drab, it is a sign that something is not right.

Simply put, plan to house your chameleon by itself.

The other issue is the purchasing of unrelated stock.

The owner calls and says that they have purchased a pair of baby Veiled chameleons and want advice on their care and eventually the conversation gets around to breeding, I ask if the babies are unrelated or siblings...

I would always recommend to anyone wishing to breed any species of chameleon that they choose unrelated stock. The choice to use unrelated chameleons is always the best direction to take unless there is no other option. With Calyptratus there are many choices available for unrelated genetic mates. Later on in this article I talk about the genetic concerns with calyptratus so I won't go on about this issue here but if you have the choice and the option exists, always opt for unrelated breeding stock.

Q. I have been looking for a chameleon and I have been told by a lot of people that the Veiled chameleons are one of the easiest chameleons to care for. Is this true?

- Josh S., Del Mar, CA

A: Well, that is a question that has two answers. Yes and No! I know that my goal here is to help clear up some of the confusion; so how is this statement helping? I would be lying to you if I said only yes or no. These chameleons are incredibly hardy. The have adapted to an environment that has random rainfall, inconsistent insect availability and wildly fluctuating temperatures. Yes, you must be an adaptable creature to survive the extremes that they face in their wild state. Yes, this means that for all those reasons they have been able to use this adaptability to live and oftentimes just survive in captivity. The result of this adaptability was the belief that they weren't as demanding in their captive requirements as other chameleons. This is also how and why the yes answer turns in to a no.

In Yemen, where C. calyptratus is found, they live in a variable and often times hostile environment with an inconsistent annual rainfall ranging any where from 4 to 80 inches per year. The temperature fluctuates from 67° to 111° F day and the nights can drop as low as 32° F and in some areas there is even an occasional frost. The calyptratus tend to live in what is called waddies or ravines where there is somewhat more protected and there is a higher density of foliage and moisture. Their insect food resources are affected by both the weather and the seasonal influxes. Their source of drinking water is also influenced by seasonal availability. Weather reports for some of the areas calyptratus inhabit have recorded times as long as three years going by without any recordable rainfall. By drinking the morning dew from the ocean mist that collects on the foliage of the plants they have adapted to the lack of available water. The ingestion of plant matter is also believed to have been another way the calyptratus is able to provide the essential water (and food) needed to insure the chameleon's survival. The seasonal increase and decrease of water, food and temperature create a significant piece of the information for us to consider in this species captive husbandry. The fact that this chameleon has evolved in this extreme and limited environment indicates that it can tolerate a great amount of adversity in its environment. Bring this chameleon into a captive situation and it seemingly thrives with the abundance it is provided. What we have to take into consideration is if we drastically change these natural parameters; we need to be prepared to expect some type of change/influence in the long-term outcomes with them in captivity.

Hopefully the final outcome will be positive. The biggest concern with any gross change in environment/food intake would show up in time, the problem is this takes many generations to see the effect. One of my personal concerns for the calyptratus is the on going dialog that they are inbred and are genetically defective. Is what we are seeing genetics or just a chameleon pushed to it limits. Pushed to grow, reproduce and produce in large numbers and then we blame the chameleon because it can't handle the demand put upon it. It is food for thought.

The problems we face today with this species are we have not drawn off the calyptratus wild habitat and diet. Understanding how this chameleon has adapted to survive its erratic and hostile environment gives us some insight to gain an understanding of its needs in captivity.

Q: I keep hearing that the calyptratus available have been too inbred and that is why they are having all the problems seen with them. Is this true?

-Claudia T., CV, CA

A: I would like to refer back to a statement I made in a previous question: One of my personal concerns for the calyptratus is the on going dialog that they are inbred and are genetically defective. Is what we are seeing genetics or just a chameleon pushed to it limits? Pushed to grow, reproduce and produce in large numbers and then we blame the chameleon because it can't handle the demand put upon it.

My personal opinion is that the main problems with the defects seen in calyptratus are the issue of captive husbandry. The easiest thing for anyone to do is blame the chameleon for our failure to understand their captive needs. In the wild the have proven their ability to thrive in less than ideal conditions. The lack of available food and water and the extremes in temperatures shows that they are very hardy. The question of realistically reproducing a similar captive environment is where we have fallen short and have fallen back on blaming the problem on the lack of genetic diversity.

These chameleons are not use to a fecundity of food or water. They are the masters of survival on less. The result of the increased availability of food is rapid growth and a quicker and higher reproductive response. The pushing of these chameleons to quickly grow and reproduce has taken a toll on the species as a whole. Females in the wild typically produce clutches of eggs that number in the 20's. In captivity females have been reported to produce as high as 80+ eggs. Wow! What a huge difference and what a demand it has on the female that produces that many eggs. I have even heard stories of females that were so heavy with eggs that they could not move off the floor of their enclosure. In the wild this would never happen and if a female did end up confined to the ground, she would most likely end up being a meal for some predator.

The other factor that figures into some of these complaints is the problem of pushing them to grow quickly. So many people have associated the malformation of bone development as a genetic problem. The usual cause of this is improper supplementation and lighting, not genetics. If a reptile is pushed to grow quickly, the necessary vitamins and minerals may not be available or assimilated for proper bone growth and formation. This condition is termed MBD or metabolic bone deficiency. Without the proper amounts of calcium and vitamin D³ the chameleon cannot absorb the calcium. The result is a softening of the bones that manifest in bowed legs, drooping casques, fracturing of the ribs and general overall bone loss/malformation. Proper lighting also plays a very important part of this equation. The chameleon utilizes D³ to bind and utilize the calcium. The source for D³ is through supplementation and a proper lighting source. Natural sunlight is the ideal source for D³ (UVB), but there is excellent artificial lighting available that can effectively provide an alternative source to sunlight.

Further disputing this concern of genetic frailty is a situation which occurred back in the 70's-80's when a small group of thirty + Chamaeleo (Triceros) jacksonii xantholophus were released in Hawaii. Today, well established, they have become considered by the Fish and Wildlife Department there as a pest. When exportation of them was available, these chameleons supplied us with the majority of the Jacksons we have. So, given the original numbers of Jacksons released, knowing they are the source for all the Jacksons supplied to us over the last decade and the total number of calyptratus that have been imported from Yemen, the case of a deficient gene pool doesn't hold up very well, if at all.

Where we can take responsibility is the area of natural selection. In nature only the strongest survive. In captivity we have a great buffing effect on the process of natural selection. Our responsibility to make sure to breed only the best of what we produce and the remaining chameleons are only intended as pets. In the long run this is a common practice in many areas of animal reproduction. Dogs that are not show/breeding quality are sold with restricted papers, requiring the owner to spay/neuter the dog. While this doesn't work with reptiles, the overall practice is sound and the intention is valid.

We need to be more responsible in our breeding of these reptiles for their sake. Genetics may have a part in this, but there are many other layers to the problem before genetics can be held as the singular problem, i.e.: the proper administration of food, correct supplementation, correct lighting/sunlight and the use of responsible breeding practices.

The fact that 1000's of calyptratus have been reproduced in captivity is a testament to their durability and adaptation. The reality is we need to reassess their husbandry needs.

Q: What should I be feeding my Veiled Chameleon? Some people say bugs and others say I need to give the vegetables too, what is right?

-Kelly McDade, Austin, TX

The Veiled Chameleon diet should include some vegetable/vegetation along with insects. It is up to the keeper to provide them with a diet/feeding regime that more closely parallels their wild food consumption. In Yemen there is a very distinct rainy season. In the rainy season there is an increase of insects as well as available water. It is during the dry periods the calyptratus must turn to alternative food and water sources. During the dry periods, it is the ingestion of plant matter that acts as a primary resource for these chameleons survival.

Offering fresh vegetables to chameleons are not as odd as one would think. Many chameleons have been observed consuming various forms of vegetation. The types of items consumed have varied from dried leaves to flowers to cut-up greens, spinach, broccoli bits, grated carrots or small pieces of fresh fruit (grapes, berries and similar types of fruit) offered in a small bowl. Another alternative is to provide small flats of romaine lettuce or other greens that are available at any garden supply store. Just make sure that they are pesticide free before you place them in the cage. Other "growing" offerings can be hibiscus, both the plant and the flowers edible as well as decorative, plus have the added bonus of additional vitamin C.

Offering young calyptratus alfalfa sprouts and pureed vegetable baby food is a way to give them a source vegetable matter in their diet. I have placed the baby food directly onto the leaves of the plants in their cage and they just lick it off.

Initially, there may not be a rush to consume these offerings but if you slow down on the quantity and availability of the insects, offering insects every other day to the adults, you will see an increase in their interest of the offered non-insect food items. Insects should be the major part of the diet, but they should not be provided exclusively.

The vitamin and mineral supplementation should be done in a reasonable manner with a variety of vitamin and mineral products offered in rotation. For further information on vitamin/mineral supplementation see our Nutrition column by Dr. Sue Donoghue in each issue.

Q: I keep hearing that if I don't breed my female calyptratus she will die. Is that really true?

-Colleen A., Claremont, CA,

If I had a dime for every time I answered that question! Well, I wouldn't be a rich man but I'd probably have a new car! I think that this is one of the most commonly spread "old-wives-tales" about this species.

The answer is a clear and resounding NO! There is no basis for this concept. The basic objective of reproduction is to make sure that the species will continue and so designing a female calyptratus to be a one shot all-or-nothing creature defeats the basic principal. A breed or die scenario! It wouldn't take long for the calyptratus to disappear altogether if this was true. The reality is that female chameleons have evolved with such reproductive efficiency that they have the ability to retain sperm, assuring reproduction without a male present. This makes the breed or die concept look pretty unreasonable.

I am aware of several hobbyists that have maintained female calyptratus well into their third and fourth year without breeding them. They were healthy viable chameleons. The idea to wait for a chameleon to reach full adult growth is a responsible and responsible approach breeding them. When a chameleon is given the time to fully develop and mature; the reproductive risks are significantly reduced vs. compromising a partially grown reptile. The age, size and health of a female should always be considered carefully before considering breeding. The breeding size of an adult female should average between 12 to 16 inches in overall length. The average age of a female to be bred should fall somewhere between 10 and 14 months.

"Baby to baby in one year" was the buzzwords in the early 1990's when calyptratus first became available. If you buy a baby (at fairly costly prices) you can turn around in one year's time and have the offspring to make your money back and then some. This has added fuel to the fire of the breed or die tale and the need to breed at an early age. Adding to this was another story that leaked out from one of the zoos working with the species about a die-off of sub-adult females. The word on the street had it that they were loosing the young females because they had not been bred. It doesn't take much to see where that leads us and over time both of these "stories" evolved into the tale of the breed or die female calyptratus.

The fundamental basis of this tale is founded in the lack of understanding of the requirements for this species. The cause of the deaths was more than likely attributed to poor nutritional and/or environmental conditions. We just misinterpreted or blamed the reptile for our lack of understanding.

Closing comments

Chamaeleo calyptratus is one of the most commonly kept chameleons. They have been a challenging and often misunderstood chameleon in the learning curve for most hobbyists working with chameleons. C. calyptratus has incredible adaptability. They are hardy, tough chameleons but like anything their hardiness is not without limits. In reality they are just as fragile in their needs as any other chameleon and this needs to be taken into serious consideration with their captive care. They have, partially due to their ability to survive less than ideal circumstances, have some of the greatest misconceptions surrounding them.

This is not intended to be the end-all article on this species, but more of an addendum to further help with our continued understanding of this unique species captive requirements and physiology. I hope that this article will further the understanding the captive care of this beautiful and unique chameleon.

Ken Kalisch

Ken Kalisch has worked with over 40 species of chameleons in the last decade. He was co-editor of the Chameleon information Network, as well as being published by Advanced Vivarium Systems dealing with his experience breeding Calumma parsonii parsonii in captivity. He was the editor of this CHAMELEONS! EZine from March 2002-March 2004.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com